When Viam’s engineering team set out to build a robotic solution for fiberglass sanding—one of the toughest jobs in marine manufacturing—we had to be able to iterate at rapid speed without being slowed down by the typical hardware challenges that come with prototyping robots. In traditional robotics development, switching a single component like a camera mid-project can mean weeks of rewriting drivers, updating interfaces, and refactoring control logic. This means your engineering team spends time debugging hardware integrations instead of solving your actual business problem. Vendor lock-in compounds this issue, forcing teams to stick with suboptimal hardware because the barrier to entry to swap out, or even test, a better option is too high.

Building our robotic sanding solution on Viam eliminated traditional hardware integration complexity, enabling us to swap and benchmark components without rewriting application code.

Building and iterating faster with Viam

Our sanding solution needed to handle the complex and variable geometry of fiberglass boat parts after injection molding while achieving high coverage with consistent pressure—requirements that demanded both precise depth perception and sophisticated motion planning and control. Here, we leveraged two key features of the Viam platform:

- Hardware abstraction layer: this allowed us to treat any depth camera or robotic arm as a standardized component with a common API. This meant we could swap between arms from different manufacturers, or different cameras, by simply updating the configuration in Viam to point to the new component. Downstream code is abstracted away from the actual hardware beneath the hood.

- Built-in motion service: this provided the complex, domain-specific inverse kinematics and motion planning out of the box so that we could focus our energy on developing the specific sanding patterns that would deliver a quality finish.

This combination gave us the flexibility to iterate quickly on hardware selection while our application logic remained stable. The Viam platform handled the complexity, letting us focus on higher-level business logic to create the sanding solution.

Optimizing hardware choices without rewriting code

When we started building the prototype, we used a popular off-the-shelf depth camera for robotic vision. With the camera mounted to the robot arm, we scanned the boat surface to create a 3D model on which to base the sanding plan. But as we pushed toward production-quality sanding, we discovered its limitations: noisy point clouds, poor performance beyond a distance of 50cm, and susceptibility to surface glare—all critical issues when scanning the complex curves of fiberglass boat parts.

This is where Viam's hardware abstraction proved invaluable. Instead of being locked into our initial camera choice, we evaluated and tested alternatives without touching our application code. We identified the Orbbec Astra 2 as a promising candidate. With Viam, it was even easier to swap out the cameras in the software as it was on the robot. All of the control logic and planning algorithms we wrote with the first depth camera worked out of the box with Orbbec because they interacted with Viam’s camera API that both options implement.

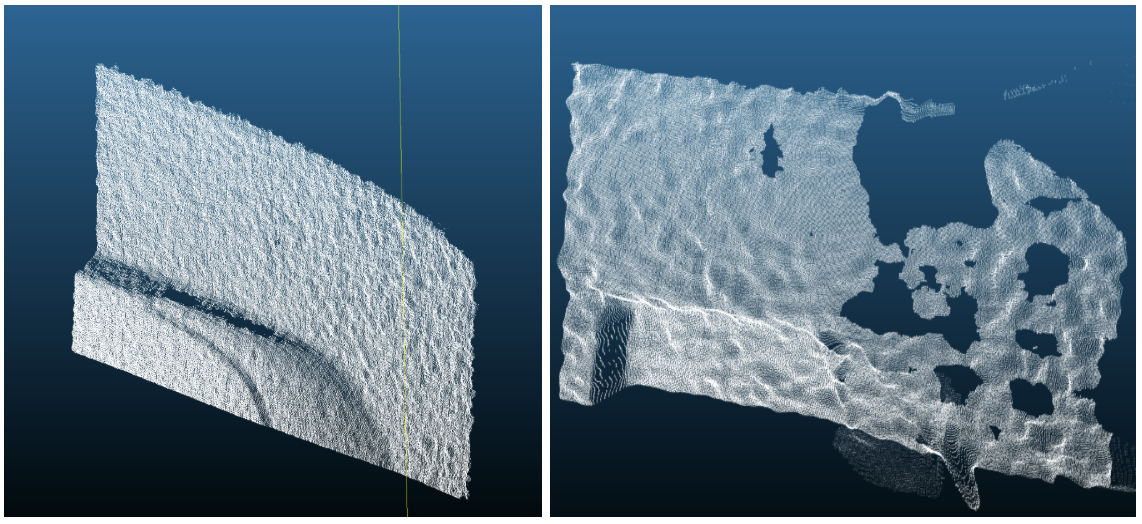

The ease of swapping also allowed us to run side-by-side tests with both cameras to get quantitative data about how they stack up with each other. The results were dramatic. At 80cm distance—critical for capturing larger surface areas in fewer scans—the Astra 2 delivered smooth, accurate point clouds while the original camera produced wavy textures with significant noise. Most importantly for our reflective fiberglass surfaces, the Astra 2's depth sensing remained unaffected by glare that created large holes in the alternative camera's point cloud.

As Olivia Miller, a Viam engineer, put it: "The Astra 2's ability to maintain accurate depth perception at 180cm completely changed our scanning strategy. We can now capture entire boat sections from a single vantage point instead of stitching together dozens of close-range scans." This rapid testing, data gathering and data-driven decision making would have been impossible without Viam's abstraction layer eliminating the traditional hardware integration burden.

.jpg)